Botany of Wolf Hollow Road

Wolf Hollow is a unique place with differing rocks and soils on either side of the road caused by a fault or slippage in the earth. (Learn more from our geology section below.) This difference in soils has created a striking difference in vegetation on each side of the trail. On the east side of the road (left side walking down) is a forest dominated by large evergreen eastern hemlocks, yellow birch, and small mountain maples. The understory is sparse with different species of ferns scattered on bare soil.On the west side (right side walking down) there is a completely different type of forest. This side is dominated by sugar maple and American basswood with scattered white ash, northern red oak, American beech, hickories, and black maple. The understory is much more diverse with many types of spring and summer wildflowers, shrubs, and ferns. Many plant species can be found along Wolf Hollow Road – try to identify them as you walk along using field guides or plant ID apps! Look for goldenrods and other wildflowers where the Chaughtanoonda Creek meanders under the road. Bring binoculars to view plants up on the slopes.

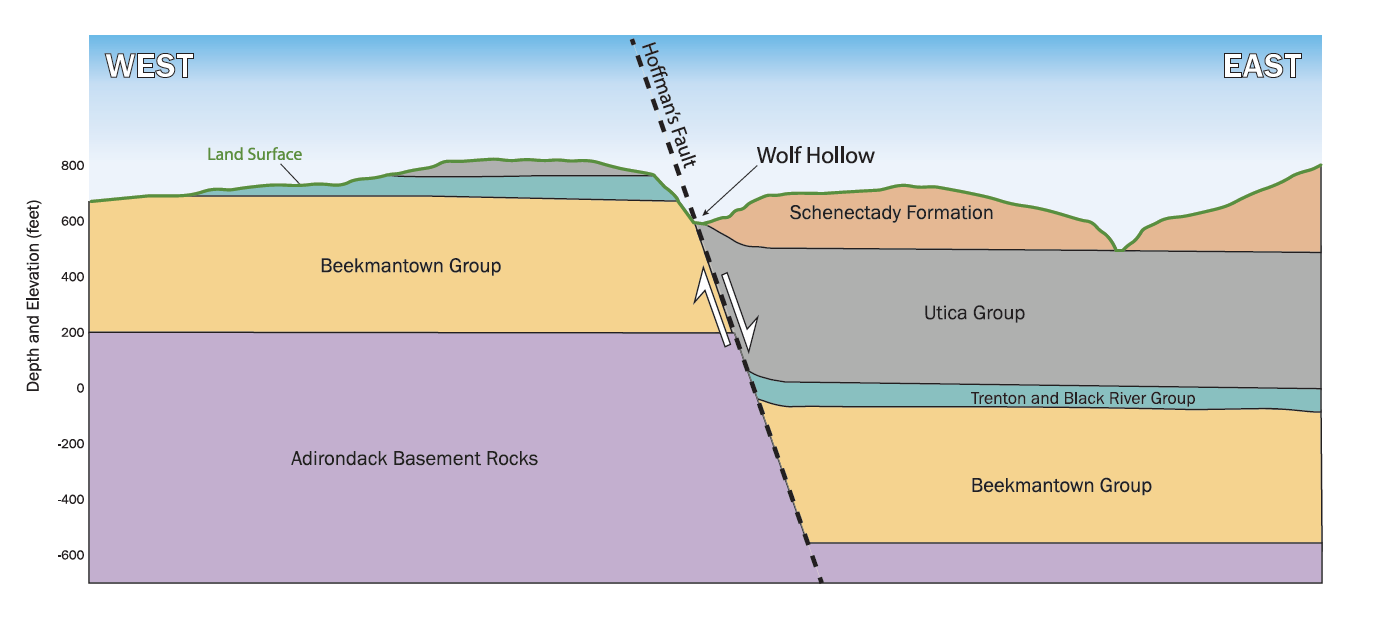

Geology Makes a Difference!

Geology significantly impacts the types of plants that can grow in a particular area. As rocks erode over time, they transform into soils with unique mineral compositions and pH levels. Shale on the east side of the road creates acidic soils favored by hemlocks and ferns. An abundance of plant species thrive in the more hospitable limestone-based soils on the west side of the road.